My Park W

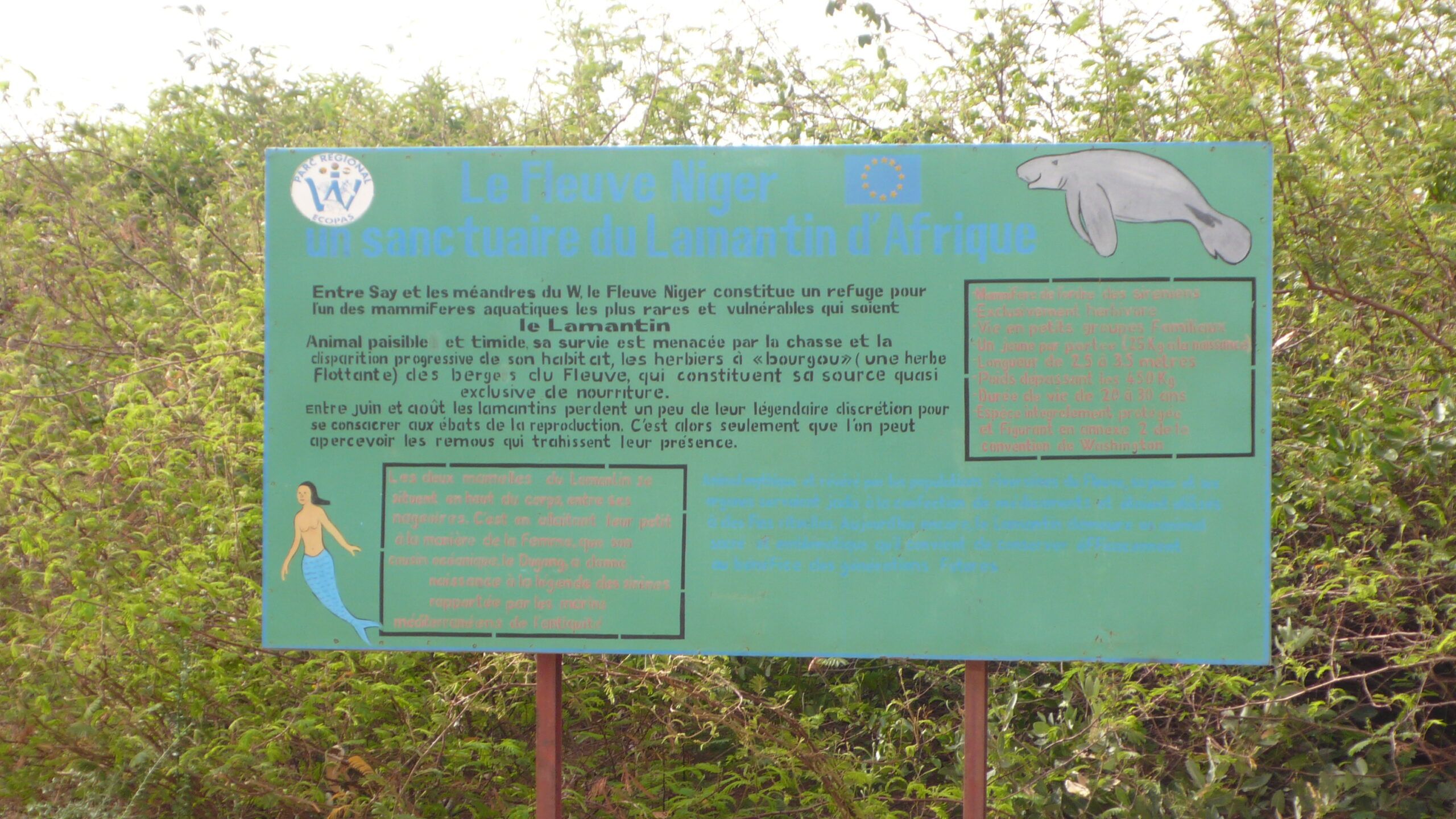

The first time I visited the W National Park was in 2002; since then, I have been there two more times, always starting from Niamey, the capital of Niger. W is a transnational park located at the borders of Niger, Benin, and Burkina Faso; the name derives from a triple bend of the Niger River, which forms a gigantic W in the middle of an intact Sudanese-Sahelian savannah, with grasslands, shrublands, wooded savannahs, and gallery forests. Together with the neighboring parks of Arly (Burkina Faso) and Pendjari (Benin), and the hunting zones of Koakrana and Kourtiagou (Burkina Faso) and Konkombri and Mékrou (Benin), W is part of the largest and most important continuum of terrestrial, semi-aquatic, and aquatic ecosystems in the savannah belt of West Africa. The total area is 1,714,831 hectares, and since 1996, this set of protected areas has been on the UNESCO World Heritage list. Here, the largest population of elephants in West Africa has been protected and still lives, along with numerous large mammals typical of the region such as the African manatee, the cheetah, the lion, and the leopard.

The first visit to W was little more than a quick excursion over a weekend. I still remember the four-hour journey from Niamey to La Tapoa, the lodge at the park entrance in “Out of Africa” style, but already somewhat neglected. No tourists, no electricity, mosquitoes, and warm beer; on the other hand, a spectacular view over the savannah. The next day, a visit down to the great river and then back to Niamey in the evening: a brief visit that left me with a great desire to return and visit it calmly. This happened in 2005 and then in 2014, during one of the last “safe” trips in Niger. Since then, the country’s security has become precarious, as has the survival of W. Although declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, this region has suffered from a historic lack of managerial and financial resources. Population growth and increasing militant extremism have severely compromised the park’s natural resources and its very survival.

For several years, Sahelian jihadists have occupied the area, turning it into a launching pad for expansion into the savannah of West Africa. Their presence is disrupting conservation efforts and local livelihoods, fueling conflicts between sedentary farmers and nomadic herders over land and water.

In 2018, two groups – the Katiba Ansarul Islam and the Katiba Serma – raided the park, gaining control of a vast area, recruiting new members among young people and herders who illegally bring their herds into the park. In recent years, jihadists have filled their coffers by taxing artisanal gold extraction around the park and trading livestock herds, as well as smuggling various goods. On the outskirts of the park, they have imposed their interpretation of Sharia, particularly on women, who have been banned from going out alone and forcing many underage girls to marry.

The authorities of the three countries have made enormous efforts – with the support of foreign partners – to halt the militants’ advance and alleviate conflicts over natural resources within and around the park through military actions, improved surveillance and anti-poaching mechanisms, and conflict resolution over resources. To ensure the conservation of fauna and flora, the management staff’s capacity of the park has been strengthened, and programs have been launched to involve local communities by adopting measures to halt the expansion of agricultural land into the park, as well as to delimit grazing areas, transhumance corridors, and resting areas for livestock. Unfortunately, the results have not met expectations. Today, the park remains a threatened, dangerous place closed to the public; its future, along with that of much of this region – where CISAO has carried out much of its cooperation work – is decidedly bleak. Looking back at the photos of my trips, I am glad to have seen it, even if a bit superficially; there remains the desire and hope to return for the fourth time, but also the fear of no longer finding that nature and atmosphere so magical.

Prof. Riccardo Fortina